Looking for a Sign: Plant Names and Garden Signs

- Kirthana Pisipati

- Jul 3, 2025

- 4 min read

by kirthana pisipati

One of my favorite projects of my fellowship so far has been compiling a list of native pollinator gardens in San Diego County to create a StoryMap for anyone to access: find the map here.

Inspired by the places I had visited so far, I aimed to include gardens that were demonstration sites or included thoughtful signage. In my research, I found gardens and preserves I had never heard of, all of which are committed to restoring habitat by planting a diverse set of native species to attract bees, butterflies, birds, bats, and more. As part of my role with the Resource Conservation District of Greater San Diego County, I help to manage and communicate with the San Diego Pollinator Alliance, a group of 21 organizations all working to study pollinators, improve their habitat, and educate the public. I reached out to our SDPA partners for input on gardens to add to my list, and I received lots of great suggestions. One person messaged back about a garden he knew of with just a set of coordinates, but I couldn’t find any information about it online to supplement the location on the map. Intrigued, I went to go see it myself to get a good picture and a description of the site.

I had my doubts as I drove up, but I was really pleasantly surprised to find a little alcove tucked away on a busy street in the middle of City Heights with a thriving native garden, a bee hotel, and an insect water feature (plus a little free library with a book I had been wanting to read for a while, Pachinko). Even more exciting was the signage that included plant names in English, Spanish, French, and Vietnamese.

Since moving to San Diego for this fellowship, I’ve been thinking a lot about names. It’s the first thing you learn when meeting someone new, and the same should go for plants, which is why I ask Who are you? instead of What are you? before I iNat a new species. It was important to me to highlight places that educate on native plant names, because people feel most connected to the natural world when they have names for what they see. One of the first times I started to learn about Indigenous names was at Chiipam hap/Spring Awakening, an event co-hosted by Tipey Joa Native Warriors and the Climate Science Alliance. Together, they had designed signs as part of the Hear Our Names project to introduce people to native plant relatives with names in English, Latin/scientific, Spanish, Cahuilla, and Kumeyaay. The signs are at gardens around the county, including at the Living Coast Discovery Center, where the event was held. The signs also include QR codes that take you to their website, where you can hear the pronunciation of the Indigenous (Kumeyaay and Cahuilla) names, voiced by Martha Rodriguez and William Madrigal Jr., respectively. The Kumeyaay language was first written down by a Dutch orthographer, and as such, can be confusingly spelled if your first language is English. As someone with a Sanskrit name unfamiliar to Western mouths, I can relate - I wanted to do justice to the plants in Southern California by learning the correct way to say their original names.

“When you play the recording or speak the name aloud, it’s the first time these plants have heard their names in thousands of years.” - Martha Rodriguez, paraphrased

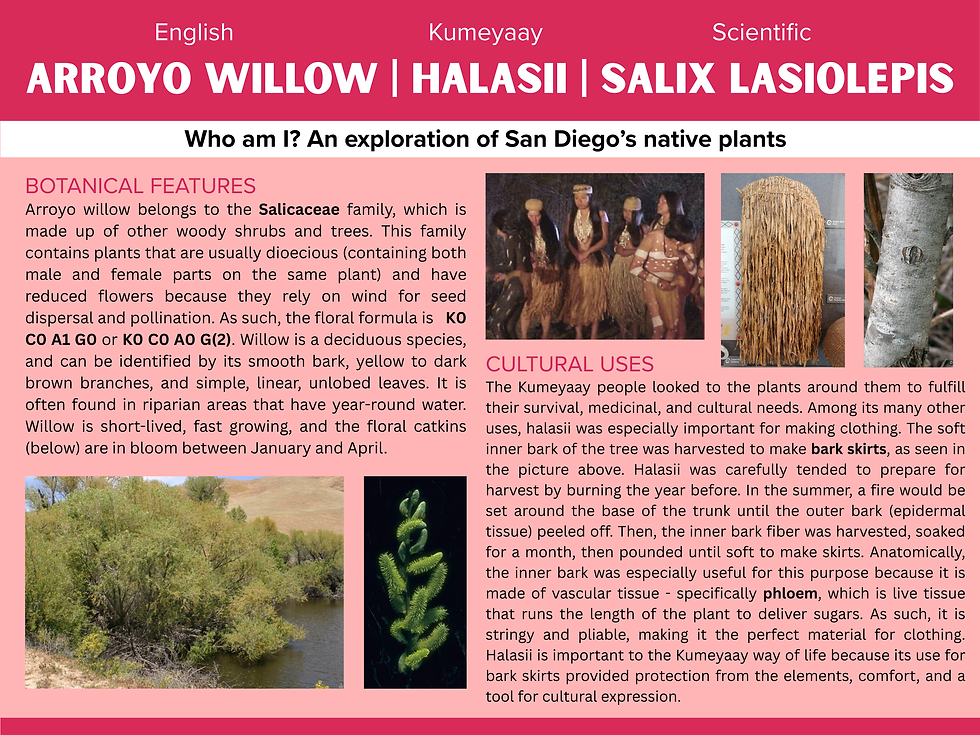

To continue learning, I took an ethnobotany class at Cuyamaca Community College in partnership with Kumeyaay Community College, taught by Michelle Garcia with help from Stan Rodriguez. I was introduced to San Diego’s native plants through the lens of Kumeyaay cultural uses, plus so many new names to learn! I often think of the quote above, and whisper to plants their original name as I pass by. I also had a full circle moment for one of my class projects where I designed a (hypothetical) sign for a pollinator garden featuring halasii, or Arroyo willow.

Beginning the work of integrating Indigenous knowledge into land stewardship and climate action starts with a name. I feel incredibly lucky as an outsider to be able to learn from members of the Kumeyaay nation through the well-developed language and culture program at the local community college. Not many tribes have been able to preserve their language so well and continue to have fluent speakers, so I’m especially aware of the significance it holds to be able to share these names with the community. I only just started learning, so it makes me happy to know that kids who grow up visiting these spaces can see the visibility of the Kumeyaay language and culture. San Diego of course also has many vibrant immigrant communities, and it’s amazing to see so many global languages represented in pollinator gardens, inviting in those who historically lack access to green space.

In the next few months, I will likely leave Southern California and meet so many new plants and learn their names. Wherever I go from here, I want to always greet plants with their ancestral names and learn what they have to offer, along with what I can offer back to them.

Comments